A Chinese 'auntie’ went on a solo road trip and now she’s a feminist icon

She spends each night alone, curled upward in a i.4m-by-2.4m rooftop tent, balanced on stilts above her motorcar. She often eats her meals in parking lots. She has seen her daughter and grandchildren but one time in the past vi months, and her hubby not at all.

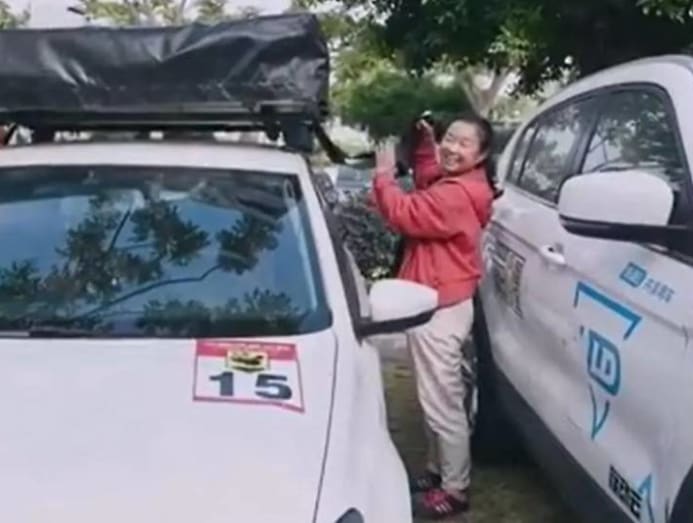

Su Min, a 56-yr-quondam retiree from Henan province in fundamental China, has never been happier. "I've been a wife, a mother and a grandmother," Su said. "I came out this time to find myself."

After fulfilling her family's expectations of dutiful Chinese womanhood, Su is embracing a new identity: fearless road-tripper and cyberspace awareness. For half dozen months, she has been on a solo bulldoze beyond Mainland china, documenting her journey for more i.35 meg followers across several social media platforms.

Her principal appeal is non the scenic vistas she captures, although those are plentiful. It is the intimate revelations she mixes in with them, nearly her abusive marriage, dissatisfaction with domestic life and newfound liberty. Her blunt but vulnerable demeanour has fabricated Su – a erstwhile mill worker with a high school education – an adventitious feminist icon of a sort rarely seen in People's republic of china.

Older women send her messages near how painfully familiar her story feels and greet her at each destination bearing fruit and home-cooked meals. For younger women, she is a font of communication most union and child-rearing. "I wish my mother could be similar Auntie Su and alive for herself, instead of being trapped and locked in by life," read a annotate on one of her videos.

Her unexpected popularity speaks to the collision of ii major forces in Chinese guild: the rapid spread of the internet and a flourishing sensation of gender equality in a state where traditional gender roles are withal deeply rooted, especially among older generations.

"Earlier, I thought I was the merely person in the world who wasn't happy," Su said in an interview from inside her beige tent. She was leaving tropical Hainan, China's southernmost province, headed for Guilin, a city famed for its lush hills, nigh 500 miles away.

Only after sharing her videos online, she said, "did I realize at that place were so many people like me."

Before last fall, Su had rarely travelled. But she had long been enamoured with the idea of driving. Growing up in Tibet, she sometimes missed the school charabanc home and had to walk 12 miles through the mountains, she said. Each time a truck passed by, she imagined sitting behind the wheel, safe and comfortable. But cars were rare, and having ane seemed impossible.

At 18, she moved to Henan and worked in a fertilizer factory. Five years later, she married her husband. They had met only a few times – not uncommon at the time – but she thought spousal relationship might be a manner out of the endless chores she shouldered at home.

Instead, she said, she plant herself laden with fifty-fifty more housework, too every bit verbal and concrete abuse. Her married man would disappear for long stretches so hit her if she asked where he had been, she said; once, he beat her with a broom.

Still, Su said, she never considered leaving, worried almost a social stigma that is still pervasive in much of Red china.

She resigned herself to her life at home. Her daughter gave birth to twins in 2017, and Su was in charge of watching them – a task that she was happy to do, just that kept her tied to her abode. Although age had cooled her husband's temper, they barely spoke. When they did, they argued.

She sought solace in novels about time-travel and romantic Korean soap operas but even so felt securely lonely. During especially heated arguments with her husband, she would faint, she said. A doctor eventually told her she had low.

So, in late 2019, she came across a video online of someone introducing their camping gear while on a solo road trip. She remembered her babyhood dream of driving – the freedom and comfort it had represented.

Over the following months, she devoured every video she could find about route trips. She took copious notes: which apps they used to find campsites, which tricks they had for saving money. (Showers at public bathhouses, she learned, could be bought in bulk).

Soon, she made up her mind: Once her grandsons entered preschool, she would embark on a trip of her own. She had bought a small white Volkswagen hatchback several years earlier, with her savings and a monthly pension of around Usa$300 (Due south$402).

Her family was resistant. Su reassured her daughter that she would be condom. She ignored her husband, who she said mocked her.

On Sep 24, she fixed her tent to the summit of the motorcar, packed a mini-fridge and rice cooker, and set off from her home in the urban center of Zhengzhou.

She posted video updates equally she drove, and in October, 1 of them went viral on Douyin, the Chinese TikTok. In it, she described how oppressed she had felt by housework and her husband.

"Why do I want to take a route trip?" she sighed. "Life at habitation is truly too upsetting."

Millions watched the video, sharing it with hashtags like "runaway wife."

Su continued beyond the country, visiting historical Xi'an, mountainous Sichuan and the onetime town of Lijiang – covering more than 8,500 miles so far. She saved on highway tolls by taking country routes. At night, she unfolded her tent atop her car like an accordion, feeling safer upwards high. Before setting out again each morn, she draped her wet towel on a clothesline strung across the dorsum seat.

In her videos, she marvelled at her new-establish freedom. She could drive as fast as she wanted, brake as hard equally she liked. At each stop, she fabricated friends, she said. Wrapping dumplings on camera in a Hainan parking lot in February, she laughed when tourists passing by asked who was travelling with her.

"I love eating hot peppers, merely my family doesn't like them, so I had to brand myself not eat peppers," she said in an interview. "Now after coming out, I tin can eat peppers every day."

She has sometimes encountered hostility. Once, she said, a man asked how she could air her family's private diplomacy and said he would beat out her if they ever met in person. She replied, "Skillful matter I haven't met you."

Su's girl, Du Xiaoyang, who visited her in Hainan last month, said her mother was a new person.

"Anything she wants to exercise, she just does, whereas before she seemed agape of everything," Du said.

In March, Net-a-Porter, the luxury shopping website, featured Su in an advertisement for International Women's Day.

Still, Su blushes when asked near her new fame. She also says she is non yet qualified to claim the pall of feminist. "It took me and then many years to realize that I had to live for myself."

She paused: "Information technology's something I'thou waking upward to, non something that I just am."

At that place are limits to what she is willing to change. Although she is determined to move out if her husband continues to care for her badly, she says she doesn't desire a divorce, knowing that her daughter would feel obliged to care for him if she left.

Simply she tries not to dwell upon that eventual homecoming. Get-go, she plans to cover all of China. That could take a few years.

"Now that I've finally come out, now that I want to leave behind that life, I demand time to let it melt away," she said. "There are many things that, every bit fourth dimension passes, may have an upshot yous never imagined."

Past Joy Dong and Vivian Wang © The New York Times

Source: https://cnalifestyle.channelnewsasia.com/travel/chinese-woman-solo-road-trip-china-feminist-icon-246571

Post a Comment for "A Chinese 'auntie’ went on a solo road trip and now she’s a feminist icon"